Topics:

Search for topics or resources

Enter your search below and hit enter or click the search icon.

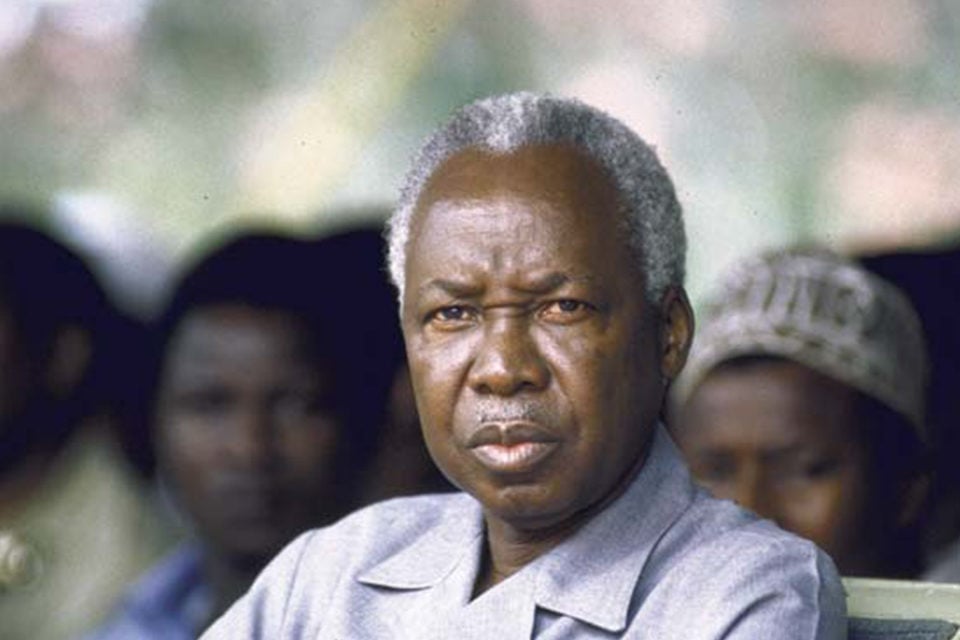

I’ve finished Kaunda. Now on to Nyerere, a contemporary of Kaunda’s who was the first president of Tanzania, serving from 1964 to 1985. I’m reading his book Socialism, which is a collection of addresses and papers he wrote in the early days of his career. I read it once years ago, but am coming back to it now for the first time in awhile.

From what I’ve read so far, I think I’m going to prefer Kaunda to Nyerere. But we’ll see. I may also loop in some stuff from James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State while I write on Nyerere, as Scott dedicates an entire chapter of his book to Nyerere’s failed project of villagization in post-colonial Tanzania.

Anyway, on to Nyerere. As we’ll see, he’s much more explicitly “socialist” than was Kaunda, but like Kaunda he attempts to repackage “socialism” and make it “African” rather than “western”:

Socialism—like democracy—is an attitude of mind. In a socialist society it is the socialist attitude of mind, and not the rigid adherence to a standard political pattern, which is needed to ensure that the people care for each other’s welfare.

The purpose of this paper is to examine that attitude. It is not intended to define the institutions which may be required to embody it in a modern society.

In the individual, as in the society, it is an an attitude of mind which distinguishes the socialist from the non-socialist. It has nothing to do with the possession or non-possession of wealth. Destitute people can be potential capitalists—exploiters of their fellow human beings. A millionaire can equally well be a socialist; he may value his wealth only because it can be used in the service of his fellow men. But the man who uses wealth for the purpose of dominating any of his fellows is a capitalist. So is the man who would if he could!

I have said that a millionaire can be a good socialist. But a socialist millionaire is a rare phenomenon. Indeed he is almost a contradiction in terms. The appearance of millionaires in any society is no proof of its affluence; they can be produced by very poor countries like Tanganyika just as well as by rich countries like the United States of America. [Ed. note: This paper was given in 1962. The nation only became “Tanzania” in 1965 after the union of “Tanganyika” with the island of Zanzibar.] For it is not efficiency of production, nor the amount of wealth in a country, which make millionaires; it is the uneven distribution of what is produced. The basic difference between a socialist society and a capitalist society does not lie in their methods of producing wealth, but in the way that wealth is distributed. While, therefore, a millionaire could be a good socialist, he could hardly be the product of a socialist society.

Since the appearance of millionaires in a society does not depend on its affluence, sociologists may find it interesting to try and find out why our societies in Africa did not, in fact, produce any millionaires—for we certainly had enough wealth to create a few. I think they would discover that it was because the organization of traditional African society—its distribution of the wealth it produced—was such that there was hardly any room for parasitism. They might also say, of course, that as a result of this Africa could not produce a leisured class of landowners, and therefore there was nobody to produce the works of art or science which capitalist societies can boast. But works of art and the achievements of science are products of the intellect—which, like land, is one of God’s gifts to man. And I cannot believe that God is so careless as to have made the use of one of His gifts depend on the misuse of another!

For what it is worth, I think Nyerere’s definition of capitalism above does him no favors and is far too simplistic. Also, as someone living in a technocratic society rather than a traditional one, I find the talk about “mindsets” a bit chilling. But that’s mostly because I’m thinking about how that sort of rhetoric functions for us: In a society held together almost entirely by coercive threat, talk about “mindsets” inevitably slides toward the totalitarian. But in a society like the one Nyerere was coming out of, that’s not necessarily true. “Changing one’s mindset,” can be as simple as a wise elder instructing a younger person about their responsibilities and duties. So while if I heard someone talking this way today, I’d be alarmed, that same rhetoric doesn’t land in quite the same way coming from someone in Nyerere’s position and writing in 1962.

More to come. There’s a lot of interest in this essay. In particular, Nyerere tries really hard to distinguish “African socialism” from Marxian socialism. For Nyerere, Marx is just another western thinker who might help African leaders at points, but who shouldn’t be followed. Nyerere sees the solution in reaching back to the resources of traditional African society, not in reaching out to take from western ideologies, be they capitalistic or Marxist.

Jake Meador is the editor-in-chief of Mere Orthodoxy. He is a 2010 graduate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he studied English and History. He lives in Lincoln, NE with his wife Joie, their daughter Davy Joy, and sons Wendell, Austin, and Ambrose. Jake's writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Commonweal, Christianity Today, Fare Forward, the University Bookman, Books & Culture, First Things, National Review, Front Porch Republic, and The Run of Play and he has written or contributed to several books, including "In Search of the Common Good," "What Are Christians For?" (both with InterVarsity Press), "A Protestant Christendom?" (with Davenant Press), and "Telling the Stories Right" (with the Front Porch Republic Press).

Topics: