Search for topics or resources

Enter your search below and hit enter or click the search icon.

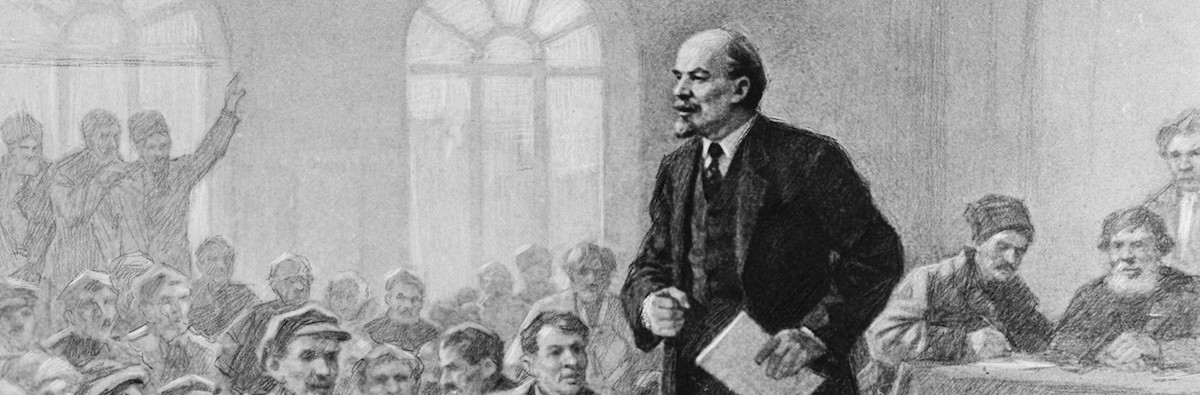

From “The Significance of Bolshevism” (written in 1933):

Man cannot live in a spiritual void; he needs some fixed social standards and some absolute intellectual principles. Bolshevism at least replaces the spiritual anarchy of bourgeois society by a rigid order and substitutes for the doubt and skepticism of an irresponsible intelligentsia the certitude of an absolute authority embodies in social institutions.

It is true that the Bolshevik philosophy is a poor thing at best. It is philosophy reduced to its lowest terms, a philosophy with a minimum of spiritual and intellectual content. It impoverishes life instead of enriching it, and confines the mind in a narrow and arid circle of ideas. Nevertheless, it is enough of a philosophy to provide society with a theoretical basis, and therein lies the secret of its strength. The lesson of Bolshevism is that any philosophy is better than no philosophy, and that a régime which possesses a principle of authority, however misconceived it may be, will be stronger than a system that rests on the shifting basis of private interests and private opinions.

And this is the reason why Bolshevism with all its crudity constitutes a real menace to Western society. For although our civilization is stronger and more coherent than that of pre-War Russia, it suffers from the same internal weakness. It needs some principle of social and economic order and yet it has lost all vital relation to the spiritual traditions on which the old order of European culture was based. As Dr. Gurian writes:

“Marxism, and therefore Bolshevism, does but voice the secret and unavowed philosophy of the bourgeois society when it regards society and economics as the absolute. It is faithful, likewise, to its morality when it seeks to order this absolute, the economic society, in such a way that justice, equality and freedom, the original war cries of the bourgeois advance, may be the lot of all. The rise of the bourgeois and the evolution of the bourgeois society have made economics the centre of public life.”

And thus:

“Bolshevism is at once the product of the bourgeois society and the judgement upon it. It reveals the goal to which the secret philosophy if that society leads, if accepted with unflinching logic.”

Later:

But although the bourgeois now possessed the substance of power, he never really accepted social responsibility as the old rulers had done. He remained a private individual—an idiot in the Greek sense—with a strong sense of social conventions and personal rights, but with little sense of social solidarity and no recognition of his responsibility as the servant and representative of a super-personal order. In fact, he did not realize the necessity of such an order, since it had always been provided for him by others, and he had taken it for granted.

This, I think, is the fundamental reason for the unpopularity and lack of prestige of bourgeois civilization. It lacks the vital human relationship which the older order with all its faults never denied. To the bourgeois politician the electorate is an accidental collection of voters; to the bourgeois industrialist his employees are an accidental collection of wage earners. The king and the priest, on the other hand, were united to their people by a bond of organic solidarity. They were not individuals standing over and against other individuals, but parts of a common social organism and representatives of a common spiritual order.

The bourgeoisie upset the throne and the altar, but they put in their place nothing but themselves. Hence their régime cannot appeal to any higher sanction than that of self interest. It is continually in a state of disintegration and flux. It is not a permanent form of social organization, but a transitional phase between two orders.

This does not, of course, mean that Western society is inevitably doomed to go the way of Russia, or that it can find salvation in the Bolshevik ideal of class dictatorship and economic mass civilization. The Bolshevik philosophy is simply the reductio ad absurdum of the principles implicit in bourgeois culture and consequently it provides no real answer to the weaknesses and deficiencies of the latter.

Jake Meador is the editor-in-chief of Mere Orthodoxy. He is a 2010 graduate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he studied English and History. He lives in Lincoln, NE with his wife Joie, their daughter Davy Joy, and sons Wendell, Austin, and Ambrose. Jake's writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Commonweal, Christianity Today, Fare Forward, the University Bookman, Books & Culture, First Things, National Review, Front Porch Republic, and The Run of Play and he has written or contributed to several books, including "In Search of the Common Good," "What Are Christians For?" (both with InterVarsity Press), "A Protestant Christendom?" (with Davenant Press), and "Telling the Stories Right" (with the Front Porch Republic Press).

Topics: